Three Ways to be Invisible

There is a common misconception that the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) was built only to search for the Higgs boson. It is intended to answer many different questions about subatomic particles and the nature of our universe, so the collision data are reused by thousands of scientists, each studying their own favorite questions. Usually, a single analysis only answers one question, but recently, one CMS analysis addressed three different new physics: dark matter, extra dimensions and unparticles.

The study focused on proton collisions that resulted in a single jet of particles and nothing else. This can only happen if some of the collision products are invisible — for instance, one proton may emit a jet before collision and the collision itself produces only invisible particles. The jet is needed to be sure that a collision took place, but the real interest is in the invisible part.

Sometimes, the reason that nothing else was seen in the detector is mundane. Particles may be lost because their trajectories missed the active area of the detector or a component of the detector was malfunctioning during the event. More often, the reason is due to known physics: 20 percent of Z bosons decay into invisible neutrinos. If there were an excess of invisible events, more than predicted by the Standard Model, these extra events would be evidence of new phenomena.

The classic scenario involving invisible particles is dark matter. Dark matter has been observed through its gravitational effects on galaxies and the expansion of the universe, but it has never been detected in the laboratory. Speculations about the nature of dark matter abound, but it will remain mysterious until its properties can be studied experimentally.

Another way to get invisible particles is through extra dimensions. If our universe has more than three spatial dimensions (with only femtometers of “breathing room” in the other dimensions), then the LHC could produce gravitons that spin around the extra dimensions. Gravitons interact very weakly with ordinary matter, so they would appear to be invisible.

A third possibility is that there is a new form of matter that isn’t made of indivisible particles. These so-called unparticles can be produced in batches of 1-1/2 , 2-3/4 or any other amount. Unparticles, if they exist, would also interact weakly with matter.

All three scenarios produce something invisible, so if the CMS data had revealed an excess of invisible events, any one of the scenarios could have been responsible. Follow-up studies would have been needed to determine which one it was. As it turned out, however, there was no excess of invisible events, so the measurement constrains all three models at once. Three down in one blow!

LHC scientists are eager to see what the higher collision energy of Run 2 will deliver.

-aTm-

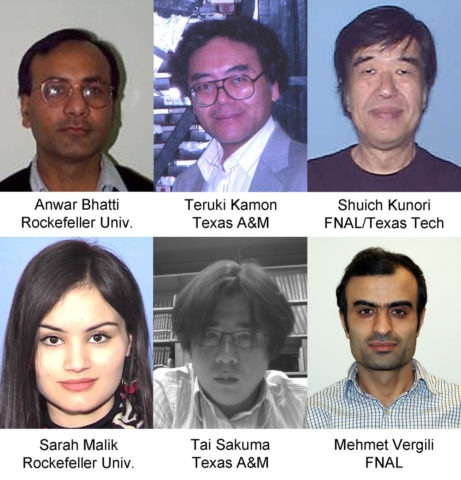

Contact: Teruki Kamon, kamon@physics.tamu.edu

The post Three Ways to be Invisible appeared first on Texas A&M College of Science