Texas A&M Physics Turns Tables on Traditional Engineering Education With Custom-Designed, Patent-Pending Laboratory Stations

On any given day, particularly during the peak hours of another busy fall semester, the 35,000-square-foot Shell Engineering Foundations Laboratory is a blur of activity, with machines humming and whirring over the din of student chatter as their mechanical arms chart patterns if not the career courses for thousands of future Aggie engineers and scientists.

The laboratory, located on the third floor of Texas A&M University’s Zachry Engineering Education Complex, is a tangible example of the transformational difference a little teamwork and Aggie ingenuity can make in improving fundamental education delivery by focusing on an old-fashioned, time-honored concept — experience — the more realistic and hands-on, the better.

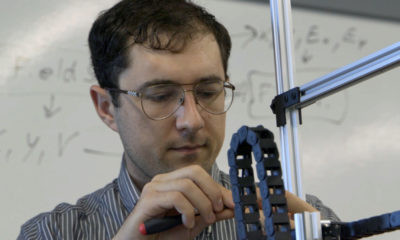

A student contemplates his next step while working at one of the laboratory’s 60 stations.

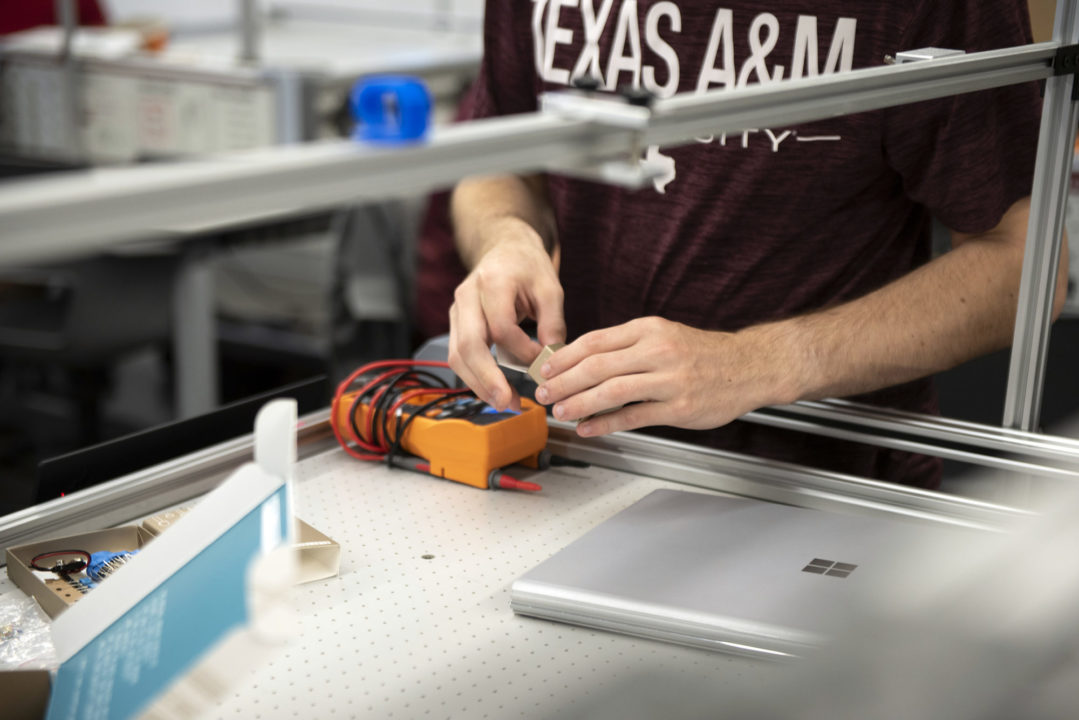

Another student adjusts a track point as part of an experiment designed to measure voltage.

Professor John Mason

Laboratory manager Alexander Yeagle makes adjustments to one of the stations, which are custom-designed and branded for Texas A&M via each information panel (below).

Texas A&M custom-built visualization studio.

Professor Ricardo Eusebi

A team of Texas A&M students discusses their current project.

You say you want a revolution

Three years ago, Zachry wasn’t the only bold renovation project underway on the Texas A&M campus. At the time, a simultaneous one began as a collaboration between faculty in the Colleges of Science and the Engineering to revamp required engineering courses, including classical mechanics, engineering calculus and chemistry for engineers. Last fall, that joint effort resulted in the campus-wide debut of an entirely new engineering physics sequence featuring not only a new set of laboratories for introductory physics service courses but also a novel method of delivery: state-of-the-art laboratory stations custom-made to revolutionize the learning experience.

Tables for 3,000

The stations consist of a high-lift, four-by-four-foot air table that provide a low-friction surface. At first glance, they resemble air hockey tables, and with students huddled around gliding brightly colored pucks back and forth, it would be easy to mistake what’s going on for a rousing bout of the popular game. In actuality, the students are analyzing detailed information on the position, velocity and acceleration of the pucks.

Committee for change

Eusebi was a member of the joint Science-Engineering committee charged in fall 2016 with merging the ENGR 111/112 classes and the PHYS 208/218 laboratories to create joint physics and engineering courses. Faculty from both disciplines as well as chemistry and mathematics met regularly for nearly a year to determine what improvements could be made to the curriculum. Beyond restructuring the course material, Eusebi says, they wanted to completely change the way it was taught. Thus, the idea for a one-of-a-kind experimental learning facility was set in motion. “It was an opportunity for us to do some research to figure out how the new labs should be designed, without any restraint on what the technology was or what devices were available,” Eusebi said. “We wanted to start completely from scratch and think of the best, most ideal lab we could have. We did that with a completely open mind.”

Conducive to collaboration

Expanding the experience

Hands-on, experiential learning is a hallmark of the Shell Engineering Foundations Laboratory, one of the largest student-serving experimental facilities on the entire Texas A&M campus.

Engineering programs at other campuses in The Texas A&M University System, including Texas A&M’s branch campuses at Galveston, Qatar and McAllen, already are embracing the technology and have implemented the new tables into their curriculum. The tables also are in use in all Engineering Academies throughout the state and in community colleges in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, Brownsville and Brenham. Thus far, 114 total units have been deployed. Last fall, Eusebi filed a patent on behalf of his team of graduate students and physicists who helped design and construct the tables. In addition, there is a company that has entered into an exclusive license with the Texas A&M System to eventually sell them commercially.

“Building these tables turned into a much bigger job than we originally thought, but a large number of colleges in Texas are using these machines and following Texas A&M’s lead,” Eusebi said.